April 26, 2021

In previous themes in this series on community economic development priorities, we have examined community members’ perceptions of COVID’s impact on local economic conditions and how resilient they believe their communities to be. Among the survey questions that we asked rural and urban Texans in the summer and fall of 2020 (for more detail about our Regional Economic Recovery Research survey methodology, click here), we included questions about their attitudes toward entrepreneurship for clues about how likely our participants might be to start or own a business. New-firm creation is a key indicator of economic health, and national data show a steady decline of startup activity across the U.S. since the Great Recession of 2008.

In light of the COVID pandemic, we wanted to ask urban and rural Texans about their current entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions. Our findings show that Texans living in urban areas have greater interest and enthusiasm to start or own a business when compared to Texans living in West Texas or rural areas. How and why do attitudes toward entrepreneurship in Texas communities differ in urban and rural areas? And what are the implications of these differences for economic growth and renewal in rural Texas?

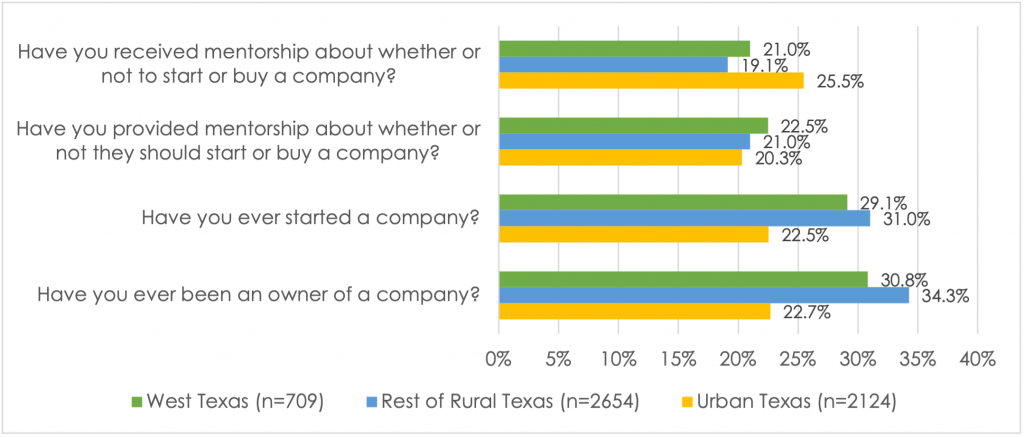

Understanding the answers to these questions starts with understanding what Texans have done in the past, both in terms of their preparation for and past entrepreneurial behavior. Figure 1 illustrates that urban Texans are more likely to have received mentorship to start a company but are less likely to have actually started or owned a company. The differences between West Texans and rural Texans are subtler, but rural Texans are both the least likely to have received mentorship and the most likely to have started or owned a company.

Figure 1 – Past Entrepreneurial Preparation and Behavior

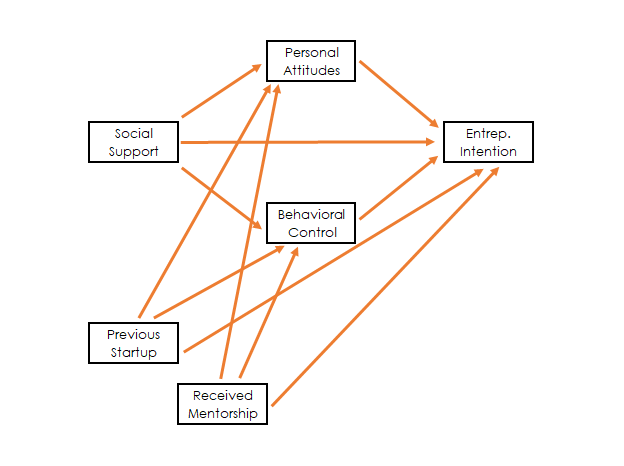

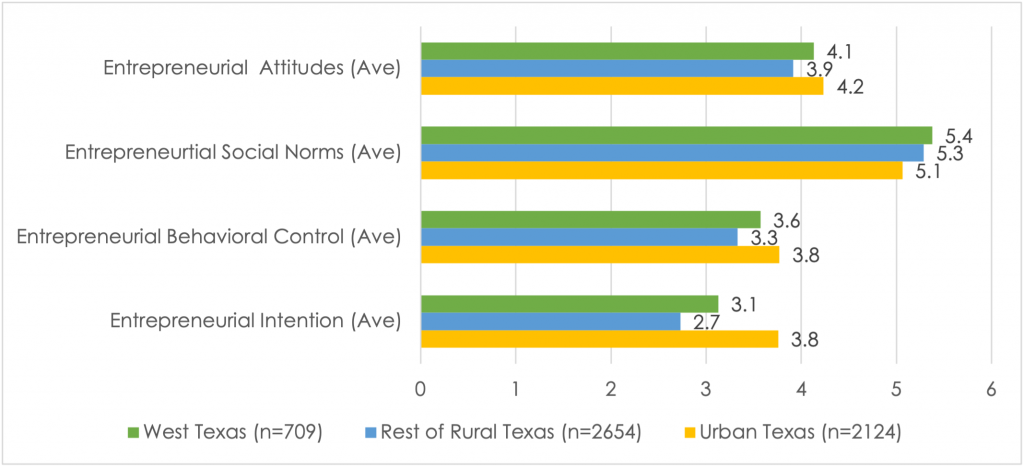

The academic literature on entrepreneurial intention (or someone’s intention to start or own a firm) suggests that there are three elements of the decision-making process that are likely to influence a person’s ability to become a business owner. Someone’s attitudes toward entrepreneurship (EA), a person’s social support network, e.g., friends, family, colleagues (SN) for that activity, and a person’s perceived behavioral control (PBC), or self-efficacy, for owning a firm all help determine whether a person will actually become an entrepreneur.[1]

We asked Texans a series of questions for each of these three antecedent themes (EA, SN, & PBC) and present the average score across those questions for each theme in Figure 2. Examples of the agreement questions we asked for each theme include:

EA

I had the opportunity and resources, I’d like to start a firm

Among various options, I would rather be an entrepreneur

SN

If you decided to create a firm, would your close family approve of that decision?

If you decided to create a firm, would your friends approve of that decision?

PBC

I can control the creation process of a new firm

If I tried to start a firm, I would have a high probability of succeeding

Essentially, these questions measure the agreement that Texans have for the strength of their attitudes about, support for, and perceived ability to succeed at entrepreneurship.

We also asked them a series of agreement questions about the strength of their entrepreneurial intentions (EI), and the average across those questions are also included in Figure 2. Example EI questions include:

I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur.

I am determined to create a firm in the future.

These findings illustrate the similarities and differences among West Texas, the rest of rural Texas, and urban Texas. In general, there do not seem to be big differences in entrepreneurial antecedents between urban and rural survey participants. But urban Texans do indicate slightly stronger attitudes toward, and more perceived behavioral control over, their intention to start or own a firm. This might be because urban respondents reported having received or provided mentorship about starting or buying a company; mentorship opportunities may simply be more plentiful in urban settings. It is also noteworthy that all Texans perceive strong social support from family and friends toward entrepreneurship.

Urban Texans do express higher entrepreneurial intentions than their rural counterparts, both in West Texas and the rest of rural Texas. Higher entrepreneurial intention in urban areas might arise from the fact that rural Texans, by necessity, have tried entrepreneurship and have experienced failure or disappointment more frequently than urban residents. Past behavior might be influencing future plans, among rural survey respondents, because entrepreneurship, by nature, is so difficult in general, and so many companies fail to thrive in any environment.

Figure 2 – Entrepreneurial Intention and Antecedents

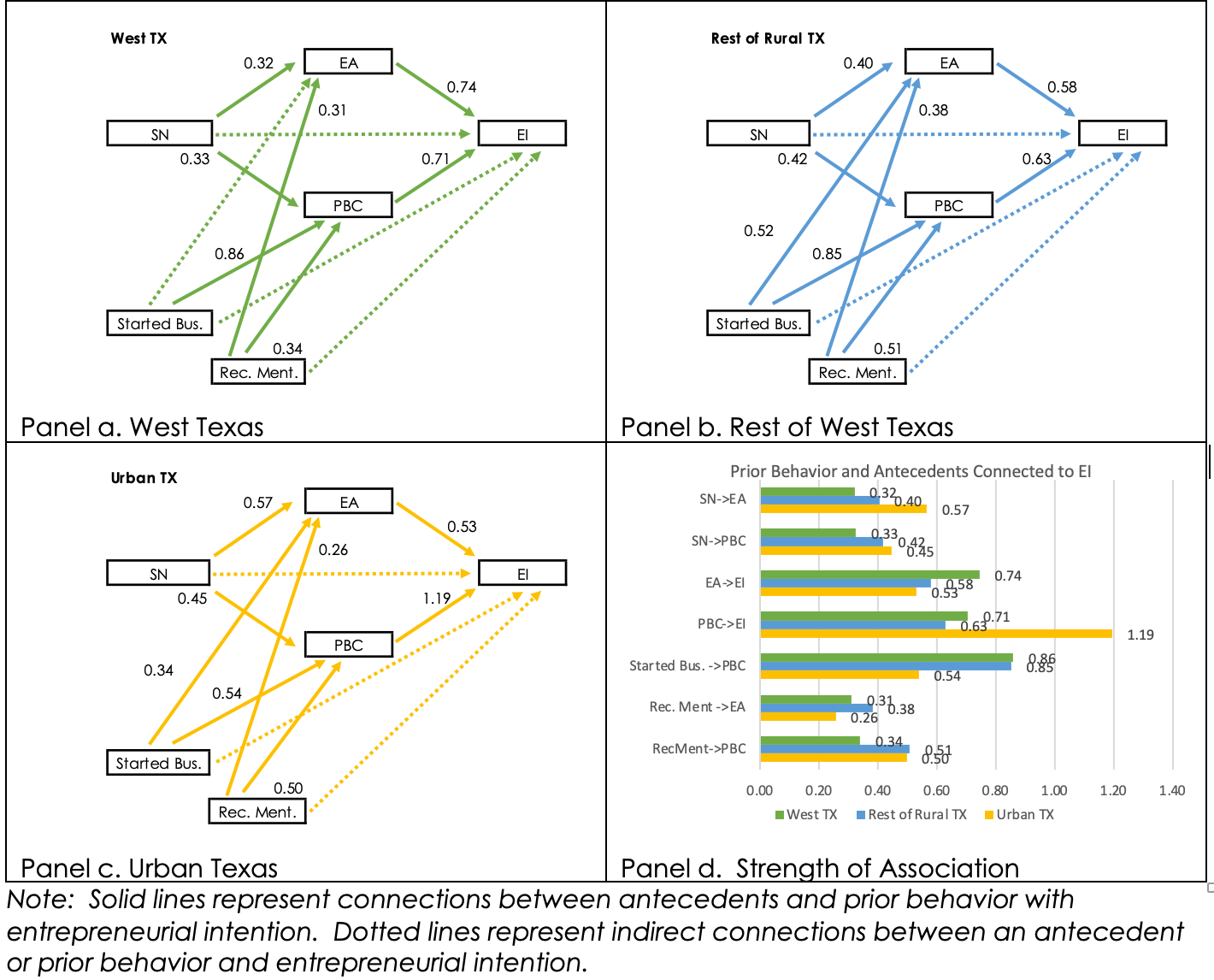

In light of this difference, an important consideration is the connection between the antecedents and entrepreneurial intention. Figure 3 illustrates how these entrepreneurial antecedents are correlated with a person’s intention to start or own a company (panels a, b, and c), with the strength of that association quantified in the bar chart in panel d. Across all regions, a person’s self-efficacy (PBC) was the most highly correlated with entrepreneurial intention (EI). And, a person’s social support network (SN) was correlated with a participant’s attitudes (EA) and beliefs about their ability to start a company (PBC). However, the connection between self-efficacy (PBC) and entrepreneurial intention (EI) was significantly stronger for urban Texans. Notably, having started a business in the past (Started Bus.) and having received mentorship in the past (Rec. Ment.) are not directly connected to entrepreneurial intentions (EI) (see dotted lines) but are connected to stronger entrepreneurial attitudes (EA) and higher self-efficacy (PBC), and thus indirectly impact entrepreneurial intentions (EI). Similarly, social support (SN) is also an indirect influence on EI (see dotted line in all three regions).

Figure 3 – Drivers of Entrepreneurship by Region

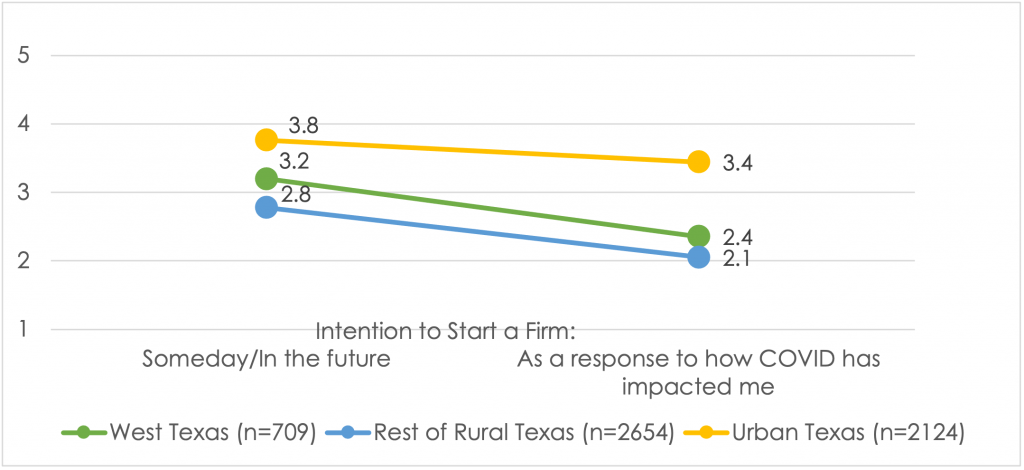

And when we asked survey participants to consider how intense their desire to be business owners was because of COVID (“I am determined/very seriously thought of/have the firm intention to start a business as a response to how COVID has affected me”), the differences between urban and rural participants were even more pronounced, see Figure 4. Somewhat surprisingly, both urban and rural participants reported lower levels of entrepreneurial intention and intensity because of COVID. One might expect that paycheck protection program (PPP) loans to small businesses during COVID might have protected smaller firms’ payrolls to a greater extent than larger firms’ payrolls, and that people laid off from larger companies during the COVID economic downturn would be more favorably inclined to be their own bosses in the future by starting or buying a company to run themselves. The survey findings, however, reveal a pullback among Texans we surveyed of entrepreneurial intention because of COVID.

Figure 4 – COVID Impact on Entrepreneurial Intention

From the findings presented here, entrepreneurial intention appears to be stronger in urban parts of Texas than in rural areas. Economic development leaders in the state should look for ways to provide more entrepreneurial mentorship, more coworking spaces and incubators, and more targeted start-up funding to West Texans and other rural Texans as an economic development tool. Innovation ecosystems in rural areas are proven avenues of rural economic rejuvenation. With the understanding that starting a business anywhere is difficult and risky, business owners in small towns can be encouraged to think big, focus on what makes their community unique, and bring new vitality to their local economies through new-firm creation.

Next: We will continue to explore local economic development and revitalization and present survey findings about how communities make tradeoffs between quality-of-life and economic development options in their communities.

We encourage your feedback and would like to hear from you. Email BBR Director, Dr. Bruce Kellison, with questions about the survey, the findings, or the analysis presented here.

Return to Regional Economic Recovery Research- Main

Return to Regional Economic Recovery Research- Main

[1] Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x